Speech acts encompass actions that can be carried out through speech, wherein the speaker says and means that they are performing a particular act. Many consider speech acts as fundamental units of communication, with the linguistic properties of an utterance helping identify the type of act being performed, such as making a promise, prediction, statement, or threat. Some speech acts hold significant consequences, as an authoritative figure can declare war or sentence someone to prison by uttering specific words.

Todd Van Buskirk’s title raises questions about the nature of promises and expectations. The use of promises regarding the number of pages between specific page numbers creates an enigmatic narrative for a “novel”:

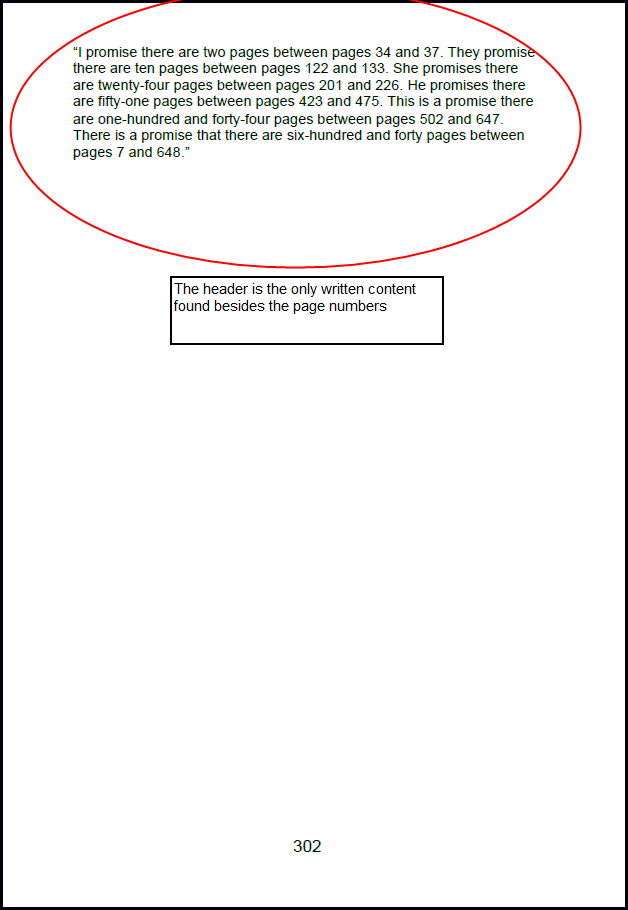

The pages referenced are either left blank or devoid of any discernible content. The title, which is also the repeated header on each page, sets the stage for a narrative that seemingly promises but the header contains the only written content besides the page numbers.

The repetition of promises with varying numbers of pages amplifies the sense of anticipation and raises questions about the author’s intent. Is Van Buskirk playing with the reader’s expectations, or is there a deeper message embedded within these empty pages? The deliberate use of specific page numbers adds a layer of precision to the promises, inviting readers to question the significance of these chosen intervals.

Certainly, the fact that Todd Van Buskirk’s promises about the number of pages between stated page numbers are accurate adds an additional layer of complexity to the narrative. In adhering to the literal fulfillment of these promises, Van Buskirk introduces a paradox within the work.

The accuracy of the page count between the specified pages might initially seem contradictory to the empty pages or lack of content, but it cleverly underscores the author’s commitment to his promises in a technical sense.

One could interpret this aspect of the work as a commentary on the duality of promises – the fulfillment of a promise on a technical level versus the expectation of substance or meaning.

By maintaining the accuracy of the page count between the mentioned promises, Van Buskirk considers the multifaceted nature of promises and whether mere numerical fulfillment is sufficient for a promise to be considered kept.

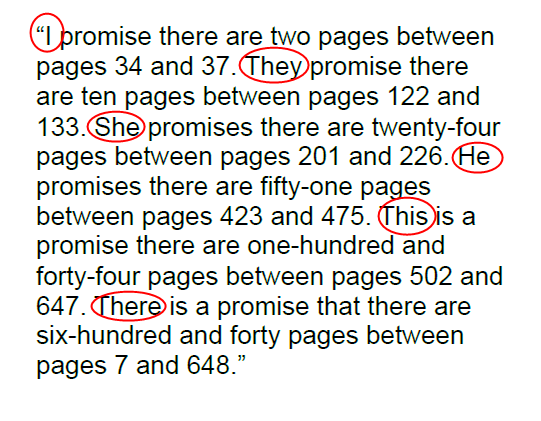

The deliberate use of different pronouns in the title paragraph adds an intriguing layer to the narrative and engages readers in a dynamic interaction with the text. The shifting pronouns, including “I,” “They,” “She,” and “He,” create a sense of multiplicity and suggest that multiple voices or perspectives are involved in making these promises.

The use of the first-person singular pronoun “I” in the initial sentence establishes a direct and personal connection between the speaker and the reader. This “I” is the one making the promise about the content of the pages, setting the stage for a unique author-reader relationship.

However, as the pronouns change with each subsequent sentence, the reader is drawn into a narrative that seems to unfold through various characters or entities.

The introduction of “They” implies a collective or plural voice, suggesting that more than one entity is involved in making promises about the content between specific page numbers.

The shift to the pronoun “She” introduces a feminine voice into the narrative. This change in perspective not only diversifies the voices within the text but also introduces a gendered element, potentially influencing the reader’s interpretation of the promises being made.

The subsequent use of “He” further diversifies the voices and introduces yet another perspective of gender.

The sentence, “This is a promise there are one-hundred and forty-four pages between pages 502 and 647,” departs from personal pronouns and instead uses the demonstrative pronoun “This.” This shift adds a layer of abstraction.

The final sentence introduces the pronoun “There,” emphasizing the existence of a promise rather than attributing it to a specific person or entity. This creates a sense of ambiguity of this overarching promise and who, if anyone, is responsible for it.

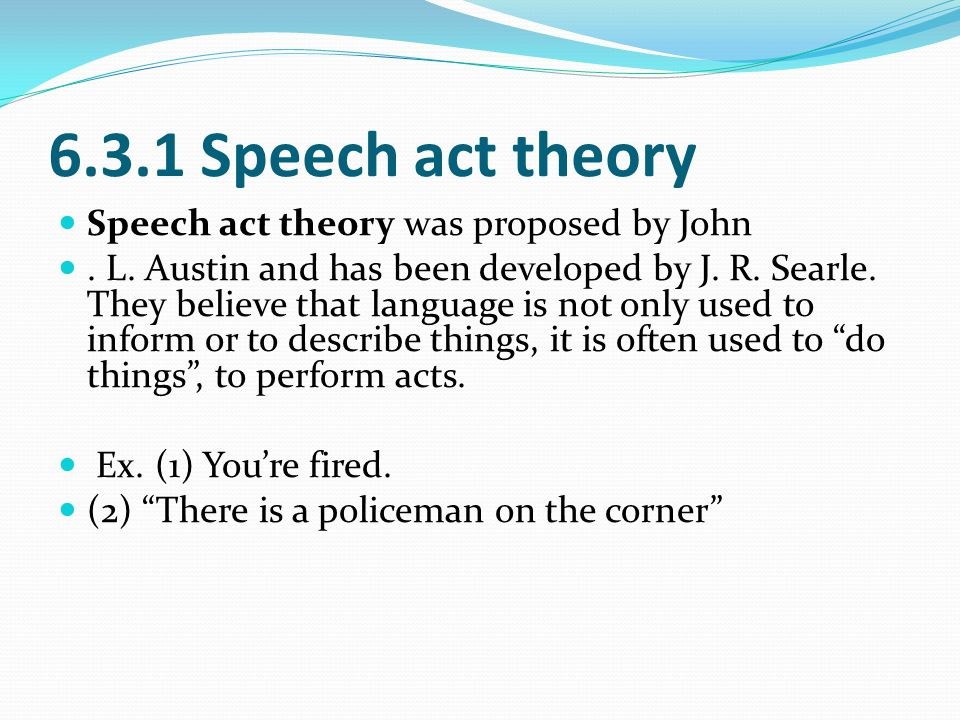

The theory of “Speech Acts” plays a role in understanding the significance of language beyond merely describing reality, and it provides a valuable framework for interpreting Van Buskirk’s unconventional use of promises in his work. Developed by philosophers like J.L. Austin and further expanded upon by John R. Searle, Speech Act Theory explores how language can be performative and go beyond the realm of statements.

Speech acts are commonly analyzed through two dimensions: the content dimension, representing what is being said, and the force dimension, representing how the statement is expressed. The grammatical mood of a sentence in a speech act indicates the force but does not uniquely determine it. Performatives, a special type of speech act, explicitly articulate the force of the utterance. Contrary to the notion that performatives like “I promise to be there on time” are neither true nor false, contemporary scholarly consensus rejects this view.

Austin distinguished between constative (descriptive) and performative (action-oriented) utterances. He argued that performative sentences, such as promises, are not just statements but actions in themselves. Van Buskirk’s promises in the title become performative acts within the realm of literature, as they go beyond mere description and actively engage the reader in a unique cognitive process.

Searle’s concept of “illocutionary force” is particularly relevant here. In the case of promises, like “I promise there are two pages between pages 34 and 37,” the performative nature of the statement lies in its ability to create a commitment or obligation for the reader. The act of promising is not merely descriptive; it is a linguistic action that shapes the reader’s interaction with the text.

However, Searle’s theory also prompts us to question the nature of these promises. If a performative formula like “I promise to…” is an “illocutionary force indicator,” it serves to make explicit the force behind the speaker’s utterance. In the context of Van Buskirk’s work, this raises the intriguing question of what kind of force or action is being invoked through promises of specific page intervals.

The paradoxical fulfillment of the promises in terms of the correct number of pages, despite the absence of traditional content, adds another layer to the discussion. It questions the conventional understanding of performative acts by demonstrating that the illocutionary force of promises can extend beyond the expected boundaries of literary content.

Searle’s concern about the presupposition that speakers can imbue their utterances with certain forces aligns with the unconventional nature of Van Buskirk’s promises. The author seems to challenge us to grapple with the normative structure within linguistic practice, urging us to consider the performative dimensions of language in the context of promises and expectations.

The interplay between Speech Act Theory and Van Buskirk’s work highlights the multifaceted nature of language, illustrating how promises, as performative acts, can transcend traditional boundaries and engage readers in a thought-provoking exploration of linguistic practice, expectations, and the nature of literary commitment.